|

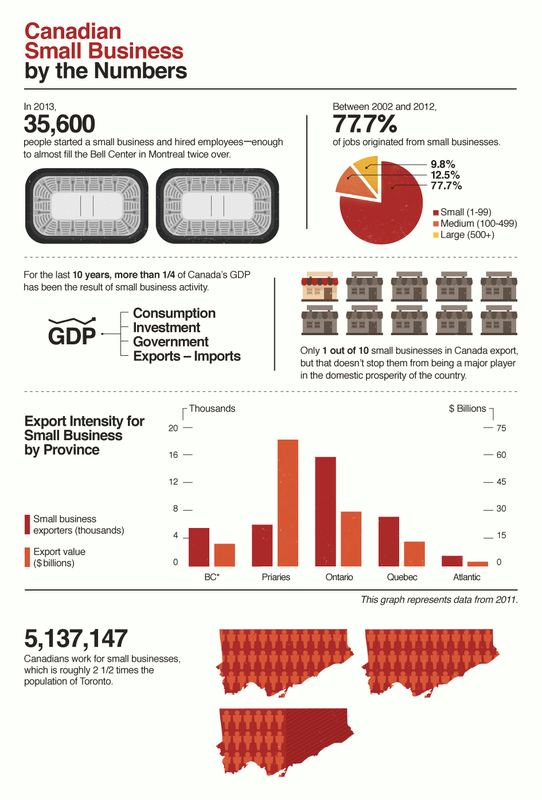

Small business in Canada looks very different compared to the corner store or independent restaurant that may come to mind. As the tech boom stretches its far-reaching tentacles across the world, there’s no set formula for small business anymore. Sure, there’s the standard mathematical definition of a small business—a company with fewer than 100 employees. But what constitutes a small business in 2014 can take on many different forms, especially as the limits of what just a few people can achieve in a short time expands. Setting out on the Small Business Path Nancy Peterson worked in senior management for Fortune 500 companies before she started her at-home business, a site where people can post reviews of home renovators and building contractors. The company has 50 employees and $5 million in annual revenue and has grown at a steady clip of 50 percent each year for the last three years. Intriguingly, it was only as the company approached 50 employees that it moved into an actual office space. The Canadian small business scene often has a lot of tech startups, which leads to local success stories of prospering businesses. Ecommerce platform Shopify, founded in 2004 out of Ottawa, now has 500 employees. Today, it’s worth millions. British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba rank in the top provinces in terms of invested venture capital. All of these areas are hotbeds for small businesses with big dreams. From Little Things, Big Things Grow: Small Business Communities The small business tradition doesn’t include just companies with plans for global domination. It also includes the micro-enterprise, or the Mom and Pop level, which is defined as having fewer than four employees. Take, for example, a married couple who owns and maintains a bed and breakfast. While they may hire groundskeepers, the occasional waiter, or concierge during busy seasons, B&B owners fit in closely with Industry Canada’s statistical picture of small businesses at the very minute end of the scale: They’re older, rely on the business as their sole source of income, and are motivated by the joys and challenges of being their own bosses. Whether it’s a young tech entrepreneur looking to grow a multinational corporation, or a couple running a bed and breakfast, small businesses rise up from communities. They carry the nation. A recent report from TD Economics estimated in the last three Canadian recessions, 85 percent of net job creation within the first two years of recovery came from small businesses. Canadians respect this. In a 2011 survey of 2,000 adults there was remarkable consensus on the value of small business to the country: 98 percent of people said small business was important to the country’s future and 94 percent of people said small business was crucial to the local community. More than two-thirds of respondents felt the government was not doing enough to help this along, a feeling partly remedied in 2013 by new support for small businesses in Canada’s Economic Action Plan. This included tax relief for new equipment, hiring credits, and better tax cuts for small businesses. An Army of Entrepreneurs: Canadian Small Businesses by the Numbers With a quick look at the numbers, it’s clear small businesses are a real cornerstone of the Canadian economy. According to theBusiness Development Bank of Canada (BDBC), there are 1.1 million small businesses in the country. Technically, 98.2 percent of all business in Canada falls into this category, with 87 percent of all small businesses comprised of fewer than 20 employees. The people running smaller companies are also a more diverse group of business leaders. Women lead one third of the small businesses, an impressive figure when compared to the total paucity of female leadership at Canada’s largest companies. Small Business Is an Emblem of Canadian Resilience Small business in Canada shows off something of the country’s national resilience: 2.7 million Canadians are self-employed. In these post-global financial crisis times, the greater Canadian economy isn’t adding jobs at a great pace. The Canadian labour force is largely static compared to five years ago. Against this trend, small business in Canada is in itself extraordinarily resilient. Despite a general economic stagnation, small businesses are the only group where employment has slowly ticked upward in the last five years. Employment in larger enterprises cratered in 2009 and is just working its way back to even. Small businesses are survivors, too. In fact, companies with fewer than 100 employees have a better survival rate than those with fewer than 500 over a two-year span: 86 percent to 80 through year one, and 85 percent to 72 percent through year two. Sure, the rate of new small businesses created may be significantly down—the 35,000 new businesses created in 2013 is just a snippet compared to the historic highs of 115,000 in 2005—but these companies are still holding their own, outshining other economic groups and supporting the country. It’s a hard working group, too. The average Canadian worked a 35-hour workweek in 2010. The average self-employed Canadian worked a 40-hour week. And 31 percent of self-employed Canadians reported working more than 50 hours a week that year. For the rest of the working population? Just four percent recounted working 50-hour weeks. Location, Size, and Industry While Ontario, with one third of Canada’s population, accounts for roughly 35 percent of all small businesses, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia have a higher density of small businesses. Small businesses in Nunavut and the Northern Territories contribute more to GDP on average ($4.2 and $3.7 million respectively), but that’s largely because of their lower populations. Compared to the larger population centers such as Ontario, small businesses in Saskatchewan, Newfoundland, Labrador, and Alberta contribute more per company to GDP. Money Makes Everything Go Around: Small Business Finances Access to capital and resources is key for small businesses trying to grow. Thirty percent of companies applied for debt financing in 2013. However, if the scope is expanded to include leasing, equity finance, and trade credit, 55 percent of companies were involved in some form of financing last year. Small businesses generally find it easy to gain access to money when they ask, with 85 percent of all applications approved. The bigger the business, the more certainty there is for a rubber-stamped application. Companies with fewer than 10 employees boasted a success rate in the lower 80 percent range. That figure rises up to 93 percent for financing applications from companies with 20 to 100 employees. Naturally, the bigger the company the higher the ask: Companies with 20 to 100 employees were borrowing an average of $680,000, while those with one to four were asking for $120,000. Innovation is a major contributor to growth, and small businesses play an important role in adding to the collective pool of intellectual property in Canada. In 2012, small businesses in Canada spent $4.8 billion on research and development, which is close to a third of the country’s total pool of R&D investment. Elsewhere, small businesses needed financing most often for working capital—machinery, vehicles, and real estate—as well as pressing needs and to a lesser, but still significant, extent with hardware and software. Conclusion Small business in Canada is a surprising ecosystem: a web of smaller enterprises combining together to provide the country with an often overlooked economic backbone. It’s an army of workers right under the nation’s proverbial nose, large and diverse, strong and resilient, and definitely not to be underestimated. This is an edited version of a post originally posted at http://blogs.salesforce.com/, by Salesforce Canada. You are free to re-edit and repost this in your own blog or other use under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License terms, by giving credit with a link to www.startupcommons.org and the original post.

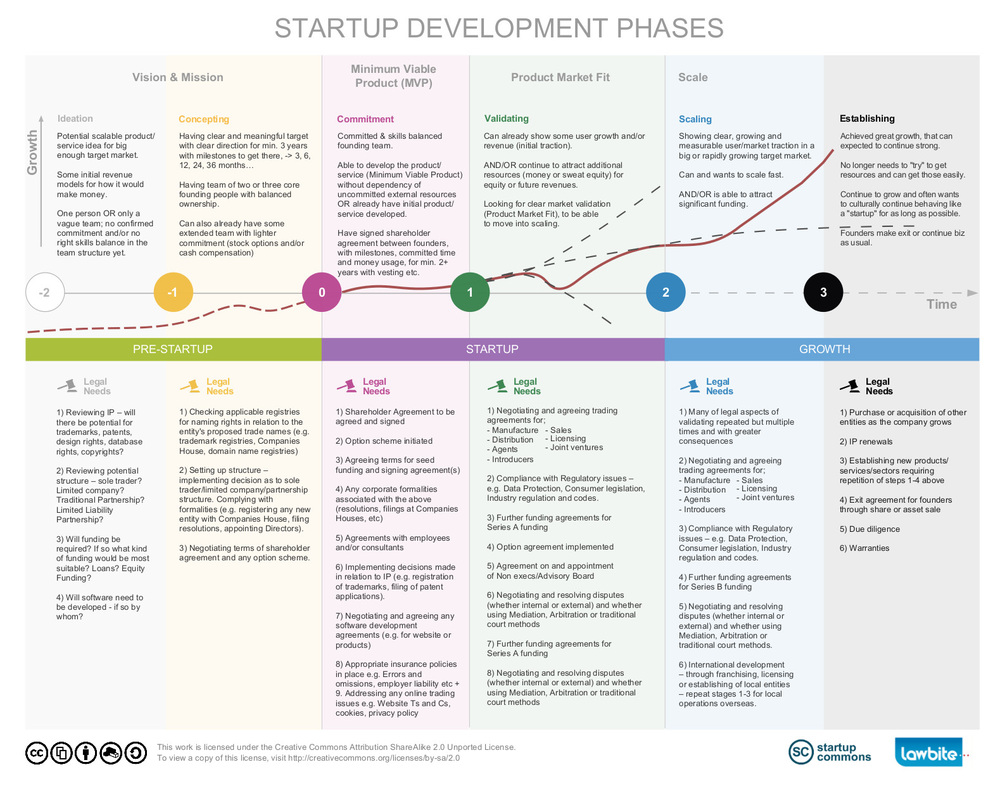

Startup Commons and LawBite have agreed to co-operate to assist small companies at every stage of their development journey. As the infographic shows, Startup Commons will be supporting them at each stage with resources, advice and best practises and LawBite will be providing legal resources for each development stage through its online platform, encompassing plain English legal documents, software and editing tools and affordable access to LawBite's virtual law firm. Startup Commons emphasise sustainability, resourcefulness and transparency in the global startup world and act as a guiding hand to the startup ecosystem. This resonates with the LawBite mantra of "Simple Law for Small companies", which seeks to democratise the law for the same small business community. Both companies recognise the need for the law to be more accessible for small businesses, so that they can be kept safe and sound at a price they can afford. PayPal founder Peter Thiel offers 12 useful tips for entrepreneurs based on his own experience in startups and investing. Aptly called ‘From Zero to One,’ his 210-page book makes for a quick and useful read, with lots of case profiles gathered along his Silicon Valley journey. He describes his book as an “exercise in thinking,” and not a manual for starting up. “Every time we create something new, we go from 0 to 1. The act of creation is singular, as is the moment of creation,” he begins. He charts two kinds of progress: linear (eg. globalisation) and non-linear (technology jumps).

“A startup is the largest group of people you can convince of a plan to build a different future,” Thiel defines. A startup sits at the sweet spot between a lone genius and a large bureaucratic organisation – size allows it to execute on ideas and smallness helps with agility. Thiel sets the context for startups by describing lessons learned from the booms and busts of the DotCom era and cleantech. Be bold, plan well, focus on sales as much as products, blend small steps with big vision, and become so good in your field that you have a sustainable monopolistic lead over the competition. Create long-term value for customers – but also extract value for your firm. Don’t just focus on the rules of the game – change the very board on which you are playing. These are expanded upon in the book’s 14 chapters. (See also other Top 10 Books for Entrepreneurs from 2013 and 2012.) 1. Breakthrough innovation or incremental improvement: where do you want to play Aspiring entrepreneurs should study growth cycles of industries they pick. Online software products can scale exponentially fast and on the global map, while many service sectors scale linearly (eg. consulting, yoga training). Some sectors are in decline (print newspapers), others have relatively short lifespans (restaurants, nightclubs) or are dependent on consumer whims (movie industry, gaming). Some sectors will thrive and endure if they ride long-term trends in tech, demography and environment (eg. rise of digital products like smartphones especially among youth; global warming). Regulation affects the activities and scope of sectors such as biotech, but not as much in software. “Numbers alone won’t tell you the answer, instead you must think critically about the qualitative nature of your business,” Thiel advises. This helps think of business opportunities a decade or more into the future. Do you want to be in a scaleable industry, or do you want to be in a linear sector with many competitors? 2. Build valuable proprietary technology “Proprietary technology must be at least 10 times better than its closest substitute in some important dimension to lead to a real monopolistic advantage,” says Thiel; otherwise it will give only short-term incremental advantage. Google search, Paypal’s online payment, Amazon’s inventory size and Apple’s design are good examples here. 3. Think big Lean and agile approaches to entrepreneurship are a methodology, not a goal – they can take you to a local maximum and not the global maximum, says Thiel. Having a big vision and plan helps deal with industry positioning. For example, Facebook turned down the $1 billion acquisition offer from Yahoo because Mark Zuckerberg could really see where his company could go, and Yahoo did not. Steve Jobs developed a long term vision for Apple with a pipeline of products for years to come. 4. Start small and leverage network effects Networks unleash powerful viral effects. But success requires starting with small networks and then scaling them. “An entrepreneur can’t benefit from macro-level insight unless his own plans begin at the micro-scale,” advises Thiel. Facebook began as a network for Harvard students, then all students and eventually anyone in the world. Don’t start with technology which works only at scale, it should grow with scale. Ideally, the potential for scale should be in the original design itself, eg. Twitter. Amazon began with only books, added similar products like CDs, and then scaled all the way. PayPal began with Palm Pilot users and eBay PowerSellers, and then kickstarted a virtuous cycle by paying early customers to sign up and get referral fees. 5. Understand the Power Law of venture capital Many startups launch and scale thanks to angel and venture capital. But many investors choose a “spray and pray” approach with diverse portfolios instead of realising that exponentially growing companies need extra attention and resources. Thiel’s Founders Fund focuses on only five to seven companies that can become multi-billion dollar firms. After all, venture-backed firms created 11% of all jobs in the U.S., with revenues accounting for 21% of its GDP; the dozen largest tech firms are all venture-backed, Thiel says. 6. Identify secrets – and go after them Thiel identifies two kinds of secrets: secrets of nature, and secrets about people. “The best entrepreneur knows this: every great business is built on a secret that’s hidden from the outside world,” he says. This calls for steady investment in innovation. HP had a good decade of innovation in the 1990s, but has now lost steam. 7. Foundations: strike the balance between ownership, possession and control “As a founder, your first job is to get the first things right, because you cannot build a great company on a flawed foundation,” Thiel explains. There should be clarity and formal documentation on ownership (equity, vesting), possession (operational authority) and control (board of directors). The trick is in finding the right balance in pay (cash, perks, equity) as well as size and composition of the board of directors. 8. Build a solid culture “A startup is a team of people on a mission, and a good culture is just what that looks like on the inside,” says Thiel. In the long run, the balance between creativity and best practices should ensure that the startup innovates, reaps the benefits of innovation effectively and continues to innovate. A culture of excitement is what creates a company that endures – not just pay and perks. Beyond professionalism, PayPal had such strong ties between its founders inside and outside the workplace that they supported each other’s ventures even after the company was sold. Among the ‘PayPal Mafia,’ Elon Musk founded SpaceX and Tesla Motors; Reid Hoffman founded LinkedIn; David Sacks founded Yammer; Steve Chen, Chad Hurley and Javed Karim founded YouTube; and Thiel himself went on to found Palantir. 9. Master marketing and sales Many techies do not have a deep enough understanding of the dynamics and inter-connects of marketing, advertising, sales and distribution, which vary in B2C and B2B sectors. Some of these activities are about creating impressions and attachment among users, others are about cultivating long-term relationships. B2B sales are complex and require ‘rainmakers,’ whereas ‘megaphone’ strategies like TV ads may be better for B2C products. “Selling your company to the media is a necessary part of selling it to everyone else,” Thiel advises, this calls for a clear public relations strategy. 10. Create a powerful brand Apple is a good example of successful branding via sleek design, branded stores, catchy ads and trademark keynotes and launches. But no technology company can be built on branding alone, cautions Thiel. 11. Think beyond ‘Dumb Data’ – use computers as tools It has become very fashionable to talk about Big Data and analytics automation, but Thiel says computers should be seen as tools which complement rather than substitute human effort. PayPal overcame its challenges in dealing with payment fraud by creating a “man machine symbiosis” between algorithms and financial experts. Thiel’s current startup Palantir also uses a human-computer hybrid to blend digital intelligence tools with trained analysts. LinkedIn does not try to replace recruiters with technology, but gives them valuable profiling tools. 12. Understand the Founder’s Paradox There are always raging debates about when it is good to have a company led by the original founder or to bring in a professional manager. Many founders, interestingly, do not neatly fall into the Bell Curve distribution of personality types – they may exhibit both extremes in themselves at different times, eg. charismatic as well as disagreeable, insider and outsider. Good examples here are Richard Branson, Steve Jobs and Sean Parker. Society should become accepting of the unusual traits of founders, but at the same founders should not expect hero worship. “The single greatest danger for a founder is to become so certain of his own myth that he loses his mind,” cautions Thiel. Thiel distills these principles in action by applying them to the cleantech boom and bust, and the few surviving success stories. Companies must not neglect even one of the seven key questions about Technology, Timing, Monopoly, Team, Distribution, Durability and Secret. Elon Musk’s Tesla has great products (even used by Mercedes), its timing to get government grants was perfect (during the cleantech boom and before the bust), it has monopoly in some segments (electric sports cars and luxury sedans), it has a crack team (like ‘Special Forces’ as compared to regular army), it controls its own distribution for better customer connect, its brand is durable, and the company has ‘secret’ insights such as fashion awareness of its customers (eg. Leonardo diCaprio). “Winning is better than losing, but everybody loses when the war isn’t worth fighting,” Thiel adds, citing examples like the legendary clashes between Larry Ellison (Oracle) and Tom Siebel (Siebel Systems). “If you can’t beat a rival, it may be better to merge,” Thiel says, citing the Paypal merger with Elon Musk’s X.com. “Beginnings are special. They are qualitatively different from all that comes afterward,” says Thiel. “Our task today is to find singular ways to create the new things that will make the future not just different but better – to go from 0 to 1 and not just 1 to n,” he concludes. ___________________________________________________________________________________________ This is an edited version of a post originally posted at http://yourstory.com/, by Madanmohan Rao. You are free to re-edit and repost this in your own blog or other use under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License terms, by giving credit with a link to www.startupcommons.org and the original post. 2. Start With Why Simon Sinek developed his very own movement by teaching us how to create movements through inspiration. His key argument is, “people don’t buy what you do; people buy why you do it.” When starting at your value proposition copy, start with why. 3. Create a sentimental bond Don Draper of Mad Men famously said; "Technology is a glittering lure. But there is the rare occasion when the public can be engaged on a level beyond flash, if they have a sentimental bond with the product." In delivering your pitch, have the courage to touch upon feelings. What these steps have in common is, they want you to tell a story that emotionally connects with your audience. You'd want to know who your audience really are, and what moves them. You'd want the story to be about them, not about you. And the minimal viable product is here to help you learn. Because, early on, you don't know what your customers want. Even your customers might not know what they want. Whether on website copy, advertisements, slide decks or in good old fashioned elevator pitches, remember, minimum viable product is not just about the product. It is an approach to finding product-market fit. For that you'd want a value proposition for what could be - a reason to exist. Make sure to check out the 7 proven templates and examples for writing value propositions __________________________________________________________________________________________ This is an edited version of a post originally posted at http://torgronsund.com/, by Tor Gronsund, Founder, Lingo Labs. Entrepreneurship lecturer, the University of Oslo and BI Norwegian Business School. Say hello at @tor. You are free to re-edit and repost this in your own blog or other use under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License terms, by giving credit with a link to www.startupcommons.org and the original post. Key to minimum viable product - your value proposition. It is about more than iterating your product on customer feedback. It is very much the big idea you'd use to guide your grand vision and ambitious long-term plan. Because in new (ambitious) markets there are few or no other products that users can compare you to. It's simply too early for users to understand how you are different. Hence, your value proposition should communicate a vision for what could be. Importantly, your 'maximum' value proposition is not finite. The best value propositions dare to be incomplete. They leave room for imagination. They focus on the bigger picture; problem, purpose, passion, love. Still, your value proposition brief is probably the earliest and minimum-ist viable product you'd develop as a lean startup. Ranging from an one-liner to a couple of paragraphs, it is the messaging you attach to whatever medium—it be an email, a news article, a website, a poster, a Google ad—that serves your minimum viable product strategy (that version of your product which allows for maximum amount of validated learning with the least effort). Here are three steps to get you going on your maximum value proposition. 1. Understand the job your customer want's to get done HBS-professor Clayton Christensen argues that a successful customer value proposition begins with genuinely understanding the customer's jobs-to-be-done -- the higher purpose for which customers buy your product. Out of the functional, social, and emotional types of jobs, the latter might be the most powerful one. Inform your user research accordingly. Are you a consultant or an entrepreneur?

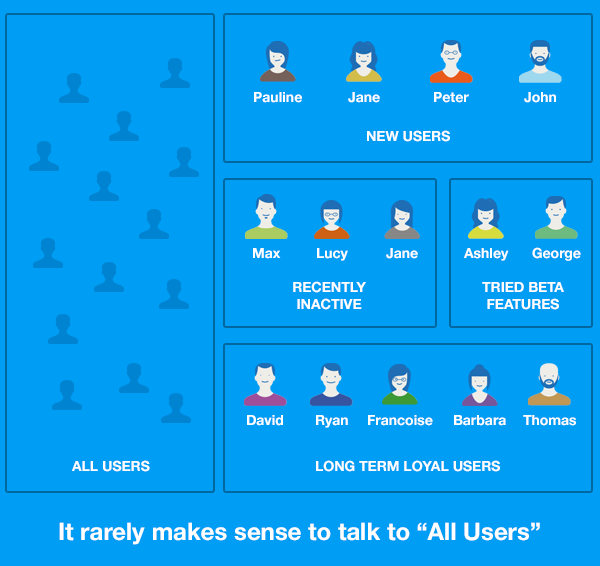

- Learn more about Growth Academy Online Training & Certification Programs Download our startup booklet and watch our videos to learn more about our framework to help startups to grow without "reinventing the wheel" and without wasting lot of time trying to connect the dots. The framework is based on the startup development phases and aims to remove the highest universal risks on the startup journey. It rarely makes sense to take feedback from all users and it never makes sense to get it all at once. At the outset of a new project, or especially if you’ve recently taken over a product, it’s tempting to survey all your users to appraise where things are. It’s usually a mistake. In fact there are five common mistakes that we see over and over. Intercom makes getting feedback extremely easy, and as a result, it’s easy to become a little trigger happy with the feedback requests. Here’s five quick fixes for product feedback: 1. Stop talking to “all users” When you survey all your users together you ignore the specifics. You mix up yesterday’s sign-ups with life long customers. Those who used your product every day with those who log in just to update billing details. Those who only use one specific feature with those who use them all. It’s a mess. Solution: There’s a much cleaner way to get much better feedback. Here’s some examples:

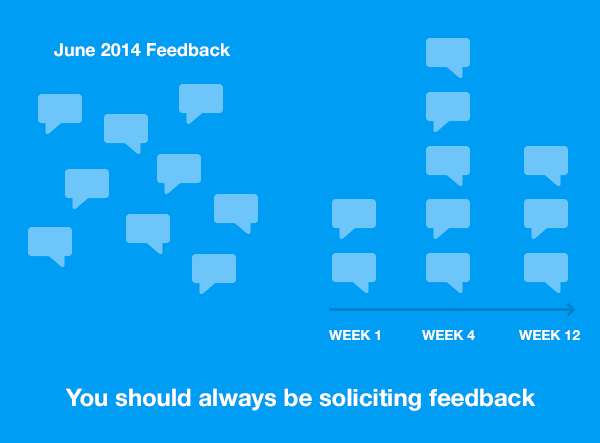

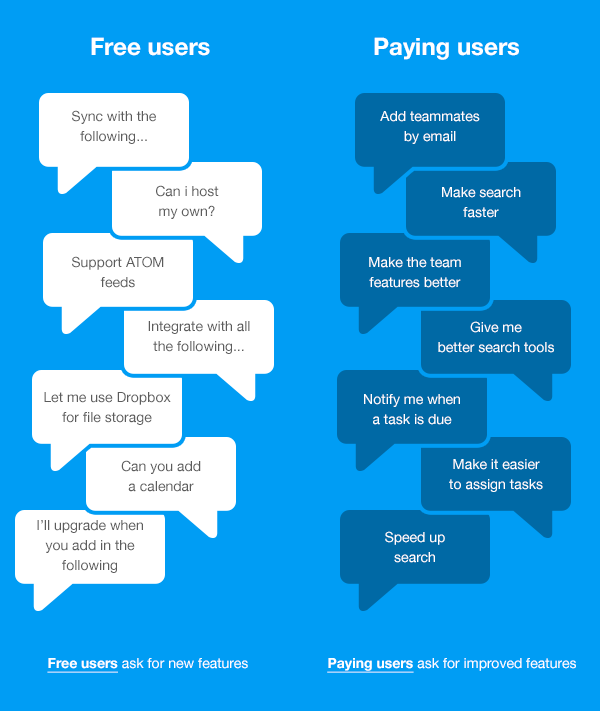

2. Feedback should be on-going The default approach to feedback is to solicit it on demand. But that means when you realise you need it you have to wait a week doing nothing while it comes in. To compensate for this you cast a very wide net, ask a lot of questions, and sit back. If you’re particularly naive you’ll act on each piece as it comes in, rather than waiting and analysing it in whole. The problem here is twofold: firstly you never have feedback to hand when you need it, but secondly you only hear about problems when you choose to ask about them. This means you’re blind to gradual degradation of your product. Solution: Periodically check in with users. The simplest, yet still valuable, version of this is to ask users for feedback on day 30, 60, 120, 365, etc. This takes about 20 seconds to set-up in Intercom, and will pay for itself in a day or two. A slightly more advanced version would be to gather feature specific feedback based on usage. For example, if you have a calendar tool, you might ask someone for their thoughts on the first, twentieth and fiftieth time they use. As a user gets used to a product their feedback matures. The first usage feedback will explain what’s confusing, the twentieth will explain the frustrations, the fiftieth will explain the limitations. 3. Distinguish Free from Paying Feedback Related to point 1, it’s easy to assume all requests are of equal value, regardless of the state of an account. This is roughly true within certain thresholds (e.g. $50->$500) but there’s a noticeable difference between the type of requests you get from free users and from paying users. Long term free users are only capable of giving you feedback on how to improve your free plan, which is rarely a focus for a business. Typically, free plans exist to draw customers in and upsell them. You can’t listen to hypothetical feedback: “I’ll upgrade if…”, “I’ll upgrade when…”. Espoused behaviour is rarely useful, learn from things that actually happened. Solution:

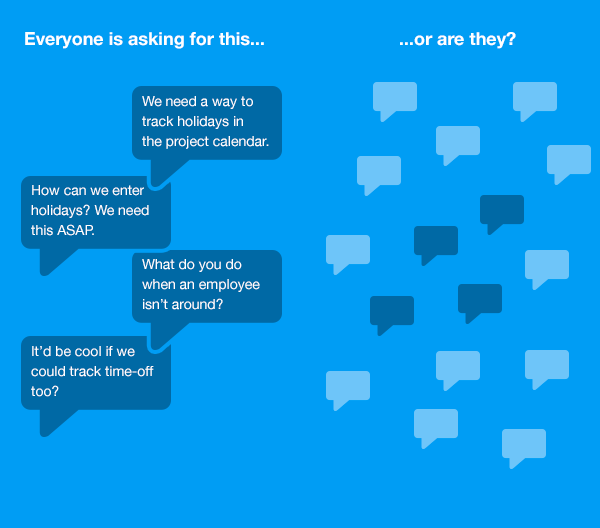

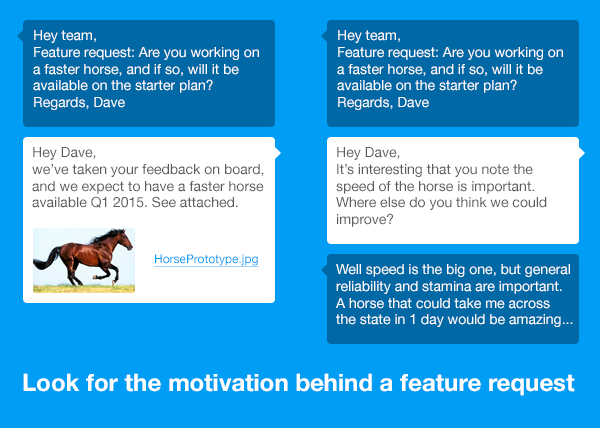

4. Don’t fall for the vocal minority It’s often said the plural of anecdote is not data, but that does not mean anecdotal evidence is not useful. The plural of anecdote is a hypothesis, or narrative. Something that’s easily verifiable. So on a day when five users ask for a simpler event form in the calendar, you don’t assume five people represent all users and immediately kick off an “event simplification” project. First you should attempt to verify if these five users represent all users. You start talking to calendar users, and see what else comes up. Solution: Treat every clustering of feedback that you see as a hypothesis, and then don’t build it, verify it. Once you verify that the pain is real, the next step is never “build the requested solution”, you have to go deeper. Which brings us to the last point. 5. Don’t assume users request the right feature To paraphrase Confucious, when customers point to the moon, the naive product manager examines their finger. The faster horses tale is often used to justify not listening to customers, but that’s an epic way to miss the point. If a customer says they want a faster horse, what they’re actually telling you is that speed is a key requirement for transport. So you think about how you deliver that. In our previous example, our friend had five people complaining that her new event form was too complex. She could have lost weeks building a natural language input, or streamlining the UX of the form, but it turns out none of that would have helped. When she talked to all the calendar users, she quickly learned the pain came not from the form complexity, but from how often it had to be used. What actually solved the pain was recurring calendar events, and making events easy to duplicate.

Solution: Be aware that customer feature requests are a cocktail of their design skills, their knowledge of your product, and their understanding of their current pain point. They know nothing of your product vision, what features you’re currently working on, or what’s technically possible. This is why it’s essential to abstract a level or two above what’s requested, into something that makes sense to you, and benefits all your customers. Of course it’s worth noting occasionally a feature request will be spot on. It will rhyme with every thing else and perfectly fit in the world the way you see it. On these occasions you can skip steps, namely verification, abstraction, and clustering and trust your gut. Your product intuition gives you wonderful shortcuts, so long as you’re still a true user of your product, and constantly in touch with the needs of your users. But on every other occasion, talk to your customers, it makes you smarter. ______________________________________________________________________________________________ This is an edited version of a post originally posted at http://blog.intercom.io, by Des Traynor, Co-founder @intercom.You are free to re-edit and repost this in your own blog or other use under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License terms, by giving credit with a link to www.startupcommons.org and the original post. “Fail Fast, Fail Often” and “Fail Better” are phrases that startups always hear from their mentors, and many live by (especially after reading The Lean Startup). Even though we’ve fully embraced the “fail fast” mantra to help our business succeed, the fear of complete failure is still there. Any startup has fears of failure. Failing fast and quickly learning from our failures helped the team at Digsy to get closer to product-market-fit before they went down in flames.

This is going to sound crazy, but one of their biggest failures was listening to their customers. This startup operates in the commercial real estate industry so the product is based on many, many conversations with potential customers: commercial real estate brokers. In every conversation, they asked about pain points, business processes and how technology could help them accomplish their goals more easily. They would hear the same things over and over, so they decided to build a product that solved common pain points and addressed their wants and needs. They did this twice, and they crashed and burned. Twice. Experimenting constantly and failing fast is a constant cycle for any entrepreneur. Every week, they try something new; if it fails (which it usually does), try something else. It is good to optimize, both on a micro- and a macro-scale. From minor messaging changes to entirely new concepts of how you can do business, everything is an experiment. It was through the series of small failures that kept their minds in the game, allowing them to see the big failure. The keys to successfully living the “Fail Fast” mantra are perseverance, urgency and validated learning . Failure is a depressing waste of time and money — if you don’t quickly learn something you can leverage toward success. Their goal from the beginning has been to improve the commercial real estate industry and change it for the better. The first product, BrokerRoster, was a tool intended to help commercial real estate (CRE) listing brokers find tenant rep brokers looking for space so they could pitch them their listings. While researching how to improve the product to generate revenue through innumerable conversations with brokers and other CRE professionals, they kept hearing essentially the same thing: “keeping track of leads and deal opportunities is too hard”. So it was decided to expand BrokerRoster to solve that pain point. Big mistake. They spent months building a suite of CRM-like tools giving potential customers what they asked for: a way to get more leads and a better way to manage deal opportunities. After all the hard work and late nights, the product enhancements failed. Very few used it and even fewer wanted to buy it. The second big failure came with the next iteration of BrokerRoster. They did more research and customer interviews and found that listing broker users kept telling them: “if you could find us more small tenants and buyers looking for space, that would be great.” Tenants and buyers that are in the market for commercial space are the lifeblood of listing brokers. Since their SaaS CRM product was failing, they again listened to customers and decided to start focusing on tenant lead generation. This time, they re-branded and built Digsy. There were two goals: help smaller, unrepresented tenants quickly find space AND help listing brokers to find tenants looking for properties like theirs. It was a win for the tenants — they could find space faster and easier — and it was a win for the brokers (at least, so we thought). Since the tenants were unrepresented, the listing broker would make more money, by not having to split the commission with another agent. They built a new service that customers asked for — a way to find more prospects for their listings — and in the process we figured out a way for them to even make MORE money. In exchange, Digsy would take a small referral fee when they closed a deal. In the first few weeks, they had many tenants using the service, going on tours and everything seemed to be going great. But as time went by, hardly any of the listing brokers who initially adopted the service were sending their listings to the tenants on our platform. This was of great concern, because it meant tenants were not getting serviced and, worse, that Digsy was failing. What the hell happened? Eventually, they wised up and realized they had failed big time. Crashed and burned. Kablooie. This product they spent five months on failed. The product all their customers asked for failed; they never used something they were so enthusiastic about. This time, they shut down for three days and sat in front of a whiteboard to discuss the state of business and explored the successes of every marketplace from Uber to 99designs. They dissected why tenants and buyers were using our product, while listing brokers could not care less. Three full days is a lot of time for a startup to put everything on hold, yet it was the defining moment. Taking a step back helped to see the big picture. It was discovered that the brokers using the system the most were not listing brokers. They were tenant rep brokers trying to find new tenants to represent. With this newfound knowledge, the service offering was reworked and they started connecting tenants with a personal market expert (broker) to help them save time & money finding commercial space. They created an on-demand network of the best market experts to help tenants & buyers find space, where the first expert to respond to a tenant or buyer request would get the business. Through these trials and tribulations, they stumbled on a product that was like Uber for commercial real estate. In the first week of modifying service they closed two deals. In the previous five months they had closed zero. Docstoc founder Jason Nazar recently shared his philosophy on failure: “Failing, as other people may see it, for me and for many other entrepreneurs, is simply part of the process of iterating until you find that thing that is meaningful and worthwhile.”JASON NAZAR, CEO – DOCSTOC A big lesson: Your customers are everything, but failing fast is only great if it is for the sake of your real customers . ___________________________________________________________________________________________ This is an edited version of a post originally posted at http://www.getdigsy.com/, by Kyle Pinzon, the Director of Customer Success at Digsy .You are free to re-edit and repost this in your own blog or other use under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License terms, by giving credit with a link to www.startupcommons.org and the original post. |

Supporting startup ecosystem development, from entrepreneurship education, to consulting to digital infrastructure for connecting, measuring and international benchmarking.

Subscribe for updates

Startup ecosystem development updates with news, tips and case studies from cities around the world. Join Us?Are you interested to join our global venture to help develop startup ecosystems around the world?

Learn more... Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

- Startup Commons

- Business Creators

-

Support Providers

- About Support Providers

- Learn About Startup Ecosystem

- Startup Development Phases

- Providing Support Functions

- Innovation Entrepreneurship Education

- Innovation Entrepreneurship Curriculum

- Growth Academy eLearning Platform

- Certified Trainers

- Become Growth Academy Provider In Your Ecosystem

- Growth Academy Training On-Site By Startup Commons

-

Ecosystem Development

- About Ecosystem Developers

- What Is Startup Ecosystem

- Ecosystem Development

- Ecosystem Development Academy eLearning Platform

- Subscribe to Support Membership

- Ecosystem Operators

- Development Funding

- For Development Financiers

- Startup Ecosystem Maturity

- Case Studies

- Submit Marketplace App Challenge

- Become Ecosystem Operator

- Digital Transformation

- Contact Us

- Startup Commons

- Business Creators

-

Support Providers

- About Support Providers

- Learn About Startup Ecosystem

- Startup Development Phases

- Providing Support Functions

- Innovation Entrepreneurship Education

- Innovation Entrepreneurship Curriculum

- Growth Academy eLearning Platform

- Certified Trainers

- Become Growth Academy Provider In Your Ecosystem

- Growth Academy Training On-Site By Startup Commons

-

Ecosystem Development

- About Ecosystem Developers

- What Is Startup Ecosystem

- Ecosystem Development

- Ecosystem Development Academy eLearning Platform

- Subscribe to Support Membership

- Ecosystem Operators

- Development Funding

- For Development Financiers

- Startup Ecosystem Maturity

- Case Studies

- Submit Marketplace App Challenge

- Become Ecosystem Operator

- Digital Transformation

- Contact Us

RSS Feed

RSS Feed